This story first appeared in the May 2017 issue of Wifi Hifi. Three years ago, a common theme in our pages was to not allow the digital world to erode the meaningful experiences that are found in what we called an analog environment. Things like reading a (physical) book, listening to vinyl, using a pencil, interacting face-to-face all seem like luxuries today in our Covid world but really, these tactile experiences may be more important than ever. Here is a look back at Gordon Brockhouse’s interview with David Sax…

LOOK DOWN ANY URBAN STREET, and you’ll see evidence of a general societal malaise: pedestrians staring intently at their smartphones, oblivious to the world around them. It’s just one manifestation of digital overload. We experience it at work, with endless PowerPoint presentations and e-mail barrages. We experience in our leisure time, with our obsessive need to check Facebook or Snapchat. When we want to listen to music or read a book, we’re overwhelmed with choice.

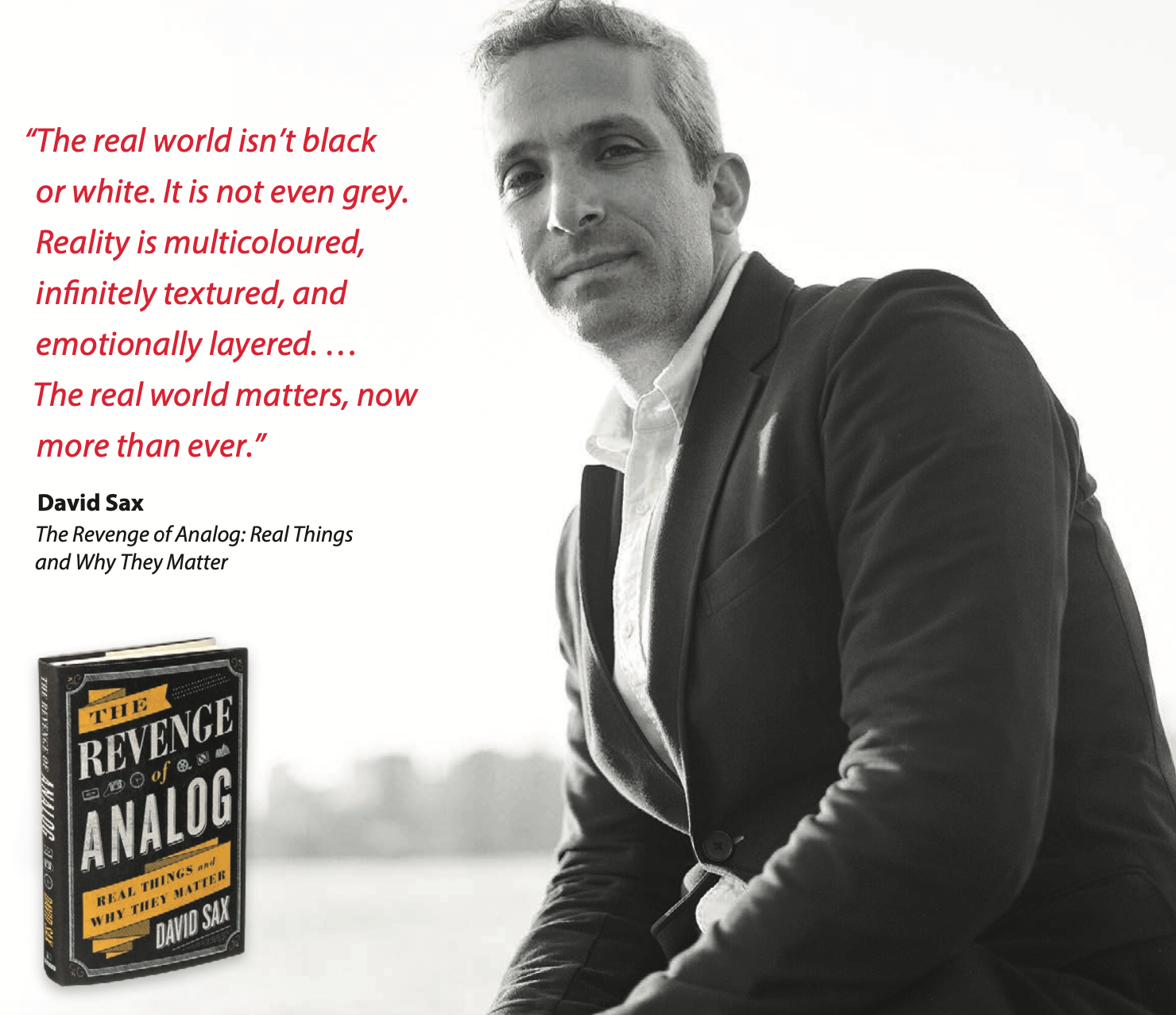

In his 2016 book, The Revenge of Analog, Toronto writer David Sax argues that people are longing for more human, more tangible experiences. Sax, whose work has appeared in Bloomberg Business Week, GQ, New York Magazine, Toronto Life and Vanity Fair, describes how different businesses are addressing this need.

Musicians and labels are releasing more and more LPs, appealing to listeners who want to collect music they love in a format they can hold in their hands. There has been a revival of independent book-stores, where readers can browse through a carefully curated selection of books. Other entrepreneurs are reviving paper notebooks, photographic film and board games.

In other chapters, Sax describes how businesses, notably those in the tech sector, are reconfiguring their work spaces and business processes to make them more human.

In the introduction to his book, Sax recounts a pivotal moment in his conversion to analog: hearing an Aretha Franklin LP playing at a local store. So fittingly, we met at Empire Espresso, a funky little café on College Street in Toronto, just a couple of doors west of June Records, where he bought that record five years ago. (Ed note: Sadly June Records closed their shop in August 2019)

Gordon Brockhouse: Something that struck me while reading your book is that the varieties of “revenge” you talk about are kind of limited. Film photography is a good example. Many of those areas are small, niche markets; and most are more accessible in big cities than smaller locales.

David Sax: I wouldn’t say that. I remember doing CBC regional interviews last fall, where I’d sit in a booth, and start in St. John’s and go to Victoria. The next day, I’d start in Gander and go to Vancouver. We’d go right across the time zones. In every city, I’d look up the local record store or bookshop. There were record stores in all these places, from St.John’s to Whitehorse. There’s a record store in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia!

With the Internet, if you’re a film photography fan, if you’re into vinyl, even in remotest Siberia, you can indulge in your passion. It’s interesting how the connectivity of the digital world gave a new life to these things. Previously, it would have been very hard for those disparate users to find each other.

GB: In your introduction, you talked about buying Aretha Franklin’s Live at the Filmore West on vinyl. Is that when you got the idea for this book?

DS: It came a long time before that. I had digitized my CD collection and done away with physical music. Immediately, my interest in music, the amount of music I listened to, just plummeted

GB: I had the opposite experience. When I digitized my library, that revived my interest in music.

DS: For me it was the opposite. It was out of sight, out of mind. That changed in 2007 when the parents of my roommate at the time were downsizing, and we acquired their turntable and record collection. I started listening to music again. I guess it was the touch and the feel of it. And that was the first time that I started noticing that there was an interest in analog, even at the time when it was supposedly dead.

GB: Are you a hi-fi nerd at all?

DS: No, no.

GB: How many LPs do you have?

DS: I have two collections: The pre-2010 collection is combined at my family cottage with my parents’ old collection. There are records I’d acquired from cousins and family, as well as stuff I bought in high school. That’s probably 400 or 500. And here in Toronto, I have 200 or 300 more.

GB: Mainly used, mainly new?

DS: Mainly used. Part of the fun for me is the thrill of the hunt. I have gotten some new pressings of older albums, but that’s not something I tend to do even though I know that’s a big part of the industry, with events like Record Store Day. So, it’s a mix, but the majority is second-hand.

GB: Any treasures?

DS: All of them! Real finds? I have a record that I bought at Cosmos Records [in Toronto] by a guy named Bola Sete, a Brazilian bossa-nova guitarist who’s played with the Vince Guaraldi Trio. It’s called Workin’ on a Groovy Thing. It just swings. He does a lot of covers: Crosby Stills Nash & Young, the Beatles, Joni Mitchell. It was one of those random finds. I wanted something Brazilian, and Aki [the store owner] pulled it out. I’ve never seen it anywhere else, and I’m in love with it. It opened that artist’s world to me.

GB: One of the promises of digital was that it would expand our choice in media. In many respects it has; but there have been losses. There was a great video store in my neighbourhood. The Film Buffhad a great staff who really knew film, and they had movies that I haven’t been able to find online. But video streaming and download sites killed them, and a lot of other stores like them.

DS: Now it’s whatever crap Netflix serves up.

GB: So the question is, has digital really expanded choice?

DS: It’s definitely expanded choice, and the choice is limitless. It’s like a Vegas buffet. You don’t really want to eat anything; you just want something sort of smaller. When I open my Spotify app, which I listen to when I’m in my car and when I’m walking, it’s just paralyzing.

I have the choice to listen to any music at any time. But what do you listen to when you can’t see it, and you’re not limited? You’ll find something, but it’s stressful.

One of the biggest attractions of the vinyl revival is record stores. Of course, you can buy records on Discogs or Amazon; but the shopping experience at places like June is 90% of the fun.

GB: Musicians universally hate streaming. In your chapter on vinyl, you mention that for some artists, vinyl is a significantly bigger revenue source than streaming. But for many musicians, getting their records into stores is always a real challenge. Is vinyl mainly an option for high-profile artists? Is it worthwhile for indie and second-tier bands?

DS: The story of the music business screwing artists over is as old as time. The reality is, if you are looking to get music out to as many people as possible, the simplest way is digital and streaming. If you want to make money off your music, you have very few options. You can play shows for money, and you can try to sell your music. If you’re a small band, and you’re able to press records and sell them for more money than they cost, then that’s cash in hand.

I’ll tell you a story. I was flying to New York with my family in November. We’re at the X-ray machine at Pearson [International Airport], and the guy in front had a whole box of records. I asked him what they were, and he said, “That’s my band.” “What’s your sound like?” I asked. “Dream Beatles,” he says. “OK,” I say, “how much?” “It’s OK,” he goes. “No I don’t want to take it. Here’s 20 bucks.”

Does that mean that that person is going to get rich off it? You can go to the dollar bin and find music by tons of artists who never made money when they had distribution. It’s a cultural product. There are no guarantees.

GB: If you were a betting man, would you bet that the vinyl revival has staying power?

DS: Absolutely. We’re now in year 10 of growth, with no signs of slowing down. Record Store Day is coming up, and there are more titles and more stores and more interest than ever. They’re selling millions of turntables a year, to an audience that has never owned one. Like any industry, there’s a period of fast growth, and then steady growth. At some point, it’ll reach a certain healthy plateau. But the market for new records continues to grow.

As somebody in the music business said, a turntable doesn’t do anything else but play records. If you have a bunch of them in the marketplace and people start selling them and losing interest, that decreases the price and gives access to more people. You get all those records being sold in places like June; but instead of $25, they’re $15.

I don’t see a reason why it would slide. People said, it’s going to go away because digital will get better. Maybe the sound quality will get better, and maybe there will be better or cheaper ways to stream music. But look: I can pull up an app on my phone and listen to anything I want, on any device I can connect the phone to. What could be technologically better than that?

GB: For your book, did you talk to artists who record in analog?

DS: I talked mainly to engineers and studio owners; and I read interviews with bigger artists as well.

GB: Is there a different mindset compared to laying down a bunch of tracks and editing them in Pro Tools?

DS: The one thing I consistently heard on that subject is that it’s not about the sound. It’s about the workflow. The technology shapes the process of recording, and that in the end influences what the music sounds like. On Lady GaGa’s latest album, they recorded several tracks in analog. The reason was to achieve a certain sound that would force her to perform in a certain way, with more urgency. One of the most interesting people I interviewed was Ken Scott, an engineer at Abbey Road Studios who’s recorded David Bowie, Duran Duran, and Beatles albums. He said, the principal advantage is that you can’t hide. There’s a performance, something happens, and you have to work with that. There are many artists who have returned to that, most of them young, from a generation who have grown up with Pro Tools and want something different.

I have no expectation that all artists are going to go analog. Even those who are using it, aren’t going to use it for every album. They will adopt recording technology based on the sound they’re looking for or the project they’re doing. What you’ll increasingly see is a mix. They might record tracks in analog, edit them in Pro Tools, then record back to tape. It’s not a question of purity; it’s what’s going to deliver the best result.

GB: In your chapter on retail, you write about the surprising rebound in bricks-and-mortar stores. You gave a very interesting example of how personal real-world retail can be: staff at Brooklyn’s Greenlight Bookstore handing customers books that might interest them. How transplantable is this type of exchange?

DS: It’s very transplantable. People go to high-end audio retailers for their expertise. The individuals working there are supposed to be the most knowledgeable. Could you get all the information you need online, in forums, review sites and specialty sites? Of course. But that approach is exhausting. There is value in a true relationship, especially if audio is a passion. Maybe someone could get a particular amp or turntable for 20% less online. But part of the fun is going into the store, checking out the gear, and listening to that $20,000 turntable. You know you’ll never buy it, but it’ll move you to something more realistic like a Pro-Ject Carbon.

GB: I’ve been told that showrooming is less common in Canada compared to the U.S. In your research, did you notice any national or regional differences in retail and consumer behaviour?

DS: In the U.S., the economics are very different. Shipping is cheap or free, and it’s quick. Here, if you’re not ordering a product from Canada, shipping is expensive. You might as well just go to a store.

GB: How big a driver do you think price is in buying decisions?

DS: In audio equipment, I think it’s major. Although the vinyl and turntable segments have grown tremendously, I don’t know if that growth has been matched in other segments. I spoke to Heinz Lichtenegger, the founder of Pro-Ject. They’ve been growing steadily since they started in 1990; but since 2008, their sales have exploded, mostly of their $300 and $400 models, and some $1,000 ones as well.

I think it’s a generational thing. Most of the people buying your average turntable today are 16-to-25 years old. How many people of that age have more than $200 disposable income? I think the percentage of them who are going to become audiophiles is probably the same as the generation before. It’s a different thing with records. A new record is around $20 or $25, which in real terms is what LPs sold for a generation ago. Used LPs fluctuate by the artist, the condition of the record, and the rarity of the title.

In terms of artists, there’s the expense of getting the record made. The reason for the tape boom is that artists who have been making records as a cheap indie thing have been priced out of the market. Now that so many records are being made, it costs more to have them pressed and distributed, so they make tapes instead.

GB: I know someone in audio who has an approach that seems analogous to what Greenlight Bookstore is doing. He purposely stays away from the demo tracks everybody uses, like “Hotel California” …

DS: Do stores actually play “Hotel California?”

GB: Apparently. But this guy looks outside the mainstream for his demo tracks. If a customer asks what music he’s playing, he knows he’s got ’em.

DS: It’s remarkable the number of times I’ve gone into June Records, and asked, “What’s playing?” The last time I was in, I asked Ian the owner, “What’s this?” He said, it’s the new record by Solange, Beyoncé’s sister. I knew her name, but had never heard her music. Thirty bucks – gone!

GB: In your chapters on the changing nature of work, you described how technology companies like Adobe and Google are using analog technologies to stimulate and capture ideas: putting them down on paper before using digital tools. Is that something that can be broadly applied?

DS: I think so. Whatever we do, all of us use various technologies, whether it’s pen-and-paper or the most advanced simulation. We work best when we use the technology that’s appropriate for the job. The one-size-fits-all solution is never a good one. If you force technology on some- one and it’s doesn’t work for that individual, then you don’t get the best results.

GB: With many employers in the service sector, work seems to have devolved into a digital tyranny. In the hospitality sector, scheduling software plays havoc with employees’ lives. CRM [customer relationship management] tools in banking and telecom leave front-line people with very little discretion in how they deal with customers. Is that a good way of doing things?

DS: It depends on your definition of “a good way.” If you’re solely focused on quarterly numbers, the bottom line and a purely quantitative analysis, the best way to manage is whatever is going to give you that input.

But we’re still human, and we respond to things on a variety of levels. A lot of them are emotional. I will go next door and buy records that I might be able to buy cheaper online, because I have a relationship here in the community. There’s a value to that.

In our work, building relationships is the strongest thing we do. The digital world can do things faster; it can do things more efficiently. Maybe for a bank that makes sense; but maybe not. When your bank closes branches and you can’t reach a human being; when everything is done through online tools or a call centre – eventually you just go to another bank.

GB: Not if there are just five banks, and they’re all doing the same thing.

DS: Then there’s an opportunity for someone to do something differently.

GB: How optimistic are you generally about people’s ability to make a dignified livelihood?

DS: I’m very optimistic about mine! That is a very interesting question about the effects of artificial intelligence, especially in certain sectors. But for every business that automates because it’s good for the bottom line, there will be opportunities for those who move in the opposite direction: for increased service, for better design, for a more human touch. Those things will command a premium.

GB: I liked your account of how Tom Kartsotis is reviving manufacturing in Detroit with his Shinola venture, and what Shinola is doing to enhance its employees’ skills. It made me want to buy one of their analog watches. Shinola is a nice story, but it strikes me as an extremely rare phenomenon, and likely to remain extremely rare.

DS: It won’t be the norm; but what it shows is that it is possible to create a business and make it profitable, and create jobs that can grow, with multiple skill levels by making things that people will buy. You have to create enough value, enough luxury to sustain the cost of what you’re doing.

I was talking about this yesterday with a reporter for the Detroit News. I said, go to the suburbs around Milan. They’re filled with luxury leather companies making things with a higher value that people pay for. That is a huge engine of that regional economy. Twenty years ago, nobody thought it would be possible to create new turntable companies. But we see new turntable brands every week it seems. There’s one that’s sprung up in Niagara Falls: Fluance.

GB: Canada actually has a vibrant audio manufacturing sector – Bryston in Peterborough, Paradigm in Mississauga, Totem and Simaudio in Montreal, to name a few – all employing 50 or 100 people to make stuff.

DS: Which is great: that’s 50 or 100 families living, working and shopping in the com- munity. There’s this fantasy that a town like Peterborough needs to attract the next Google. Once there’s a billion-dollar company in town, that will pave the whole region with gold. But you can’t build a community based on that type of gamble. You need a lot of stores and businesses and people doing different things. That’s the foundation of the middle class.

GB: I really enjoyed your epilogue, where you wrote about the summer camp you attended as a boy, and its current policy of banning cell phones and other gadgets so that kids can get a true camping experience. Do we need to take a break from technology now and then? And should it be longer than a two-week sabbatical?

DS: I strongly think so. The studies are coming out; this stuff has serious effects on our health, and we need a break from it now and then.