A new study from Juniper Research has found that merchant losses to online payment fraud will exceed $206 billion cumulatively for the period between 2021 and 2025. This figure, equivalent to almost 10 times Amazon’s net income in the 2020 financial year, demonstrates why merchants must make combatting fraud, through the use of machine learning-based fraud prevention platforms, an immediate priority.

The research identified that the pandemic has led to a surge in synthetic identity and account takeover fraud, which threaten the security of entire accounts, alongside associated payment data. The research recommends payment fraud detection vendors focus on partnering on data agreements now, to maximise the data available to machine learning algorithms, boosting chances of identifying fraudulent transactions. The research also found that spending on fraud detection and prevention platform services will exceed $11.8 billion globally in 2025, from $9.3 billion in 2021. Accordingly, the Juniper research recommends that fraud detection and prevention vendors focus on building platforms that can cover all the emerging channels of payment traffic, including new areas such as open banking payments, supported by data partnerships, and backed by large-scale machine learning, to achieve the best outcomes.

Digital payments, already a booming industry before the COVID-19 pandemic, have since been a key part of a social distancing strategy used by governments around the world. Since the pandemic, record numbers of online payments are being processed across all channels. Juniper Research forecasts that digital wallet users will exceed 4.4 billion globally in 2025, from 2.6 billion in 2020.

From market data, it is clear that online payment is convenient and drives eCommerce. However, it has also created a playground for cybercriminals who are intent on circumventing the structures on which online payments rely. Trust, it seems, is breaking down.

This finding leads to the idea of establishing ‘zero trust’ payment ecosystems that offer an option to always verify, never trust or store, with security measures, including tokenisation is providing the backbone to achieve digital payment safety.

The threat landscape continues to evolve and test existing anti-fraud measures. The omnichannel retail environment, fuelled by changing customer expectations, restrictions during the pandemic, along with initiatives that are encouraging the open use of financial data, are creating a perfect storm for fraud. Fresh and upgraded challenges must be tackled in the world of online payments. New types of fraud such as ‘silent fraud’ and cybersecurity vulnerabilities are all contributing to a complex mix of attack vectors.

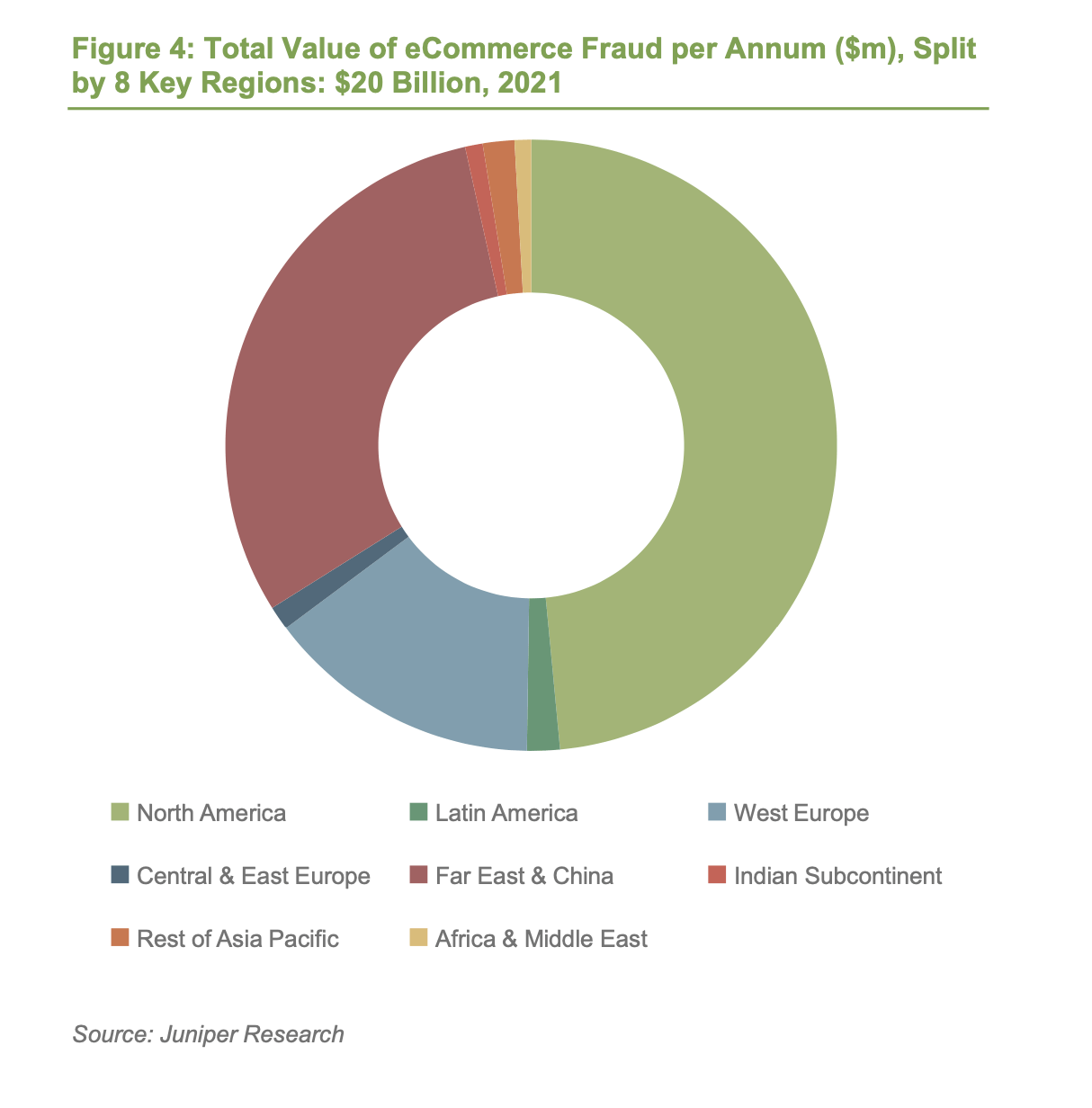

Juniper estimates the value of losses due to eCommerce fraud will rise this year, from $17.5 billion in 2020 to over $20 billion by 2021; a growth of 18% over a single year. Fraudsters have targeted consumers as they have increased their eCommerce use, exposing insecure fraud mitigation processes from merchants who are unfamiliar and unprepared with the continuing fraud challenges in this market.

While merchants will be keen to reduce fraud rates from their current levels, they will also be hesitant to introduce extra safety and verification measures into the checkout process that could discourage eCommerce.

Juniper sees China as the largest single eCommerce fraud market in the world accounting for over 40% of eCommerce fraud losses globally in 2025, at over $12 billion. China’s massive eCommerce market and a relative lack of fraud detection and prevention platform deployment are the key drivers behind this. Merchants operating in China should invest in fraud detection and prevention now, or they will increasingly face damage to their already slim operating margins.

Juniper outlines the following as new and emerging fraud techniques:

Silent Fraud – In this type of fraud, small amounts are taken from thousands of accounts – the total adding up to often more than a single large fraud event. Keeping under the radar is a tactic used in other cybercriminal techniques, for example, in detection evasion by malware. It makes sense that fraudsters will use detection evasion in fraudulent activity around payments.

Clean Fraud – is a transaction that passes a merchant’s typical checks and appears to be legitimate, yet it is actually fraudulent. For example, the order has valid customer account information, an IP address that matches the billing address, accurate AVS (address verification service) data and card verification number, etc. With clean fraud, the fraudster has managed to steal every piece of data required to carry out a purchase). Clean fraud is very difficult to combat because there are no anomalies to detect. The only option is to ask more questions, but this introduces friction to the buying process.

Friendly Fraud – occurs when a merchant receives a chargeback because the cardholder denies making the purchase or receiving the order, yet the goods or services were actually received. In some instances, the order may have been placed by a family member or friend that has access to the buyer’s cardholder information.

Chargeback Fraud – similar to friendly fraud, as a chargeback request is made in spite of received goods and services. While friendly fraud is non-malicious in nature, chargeback fraud is a premeditated intention to commit fraud.

Affiliate Fraud – this type of fraud involves the fraudulent use of a company’s lead or referral programs to make a profit. For example, companies may submit false leads with real customer information, or inflate web traffic to increase their payout before the merchant is aware of the scam.

Reshipping – this typically involves fraudsters recruiting an innocent person (known as a ‘mule’) to package and reship merchandise purchased with stolen credit cards. Since the mule has a legitimate shipping address, the merchant would have no reason to suspect fraud. The fraudsters then ask the unsuspecting individual to repackage and send the goods to them.

Botnets – a botnet is a network of infected machines controlled by a fraudster (the ‘botmaster’) to perpetuate a host of crimes. In the case of eCommerce the infected device could be used with stolen payment and identity information, so the transaction appears to originate from a location that reasonably matches the credit card in use. In this way, infected computers appear to be ‘good’ when, in fact, they are not.

Phishing – is the practice of sending seemingly official emails from legitimate businesses to steal sensitive personal information from customers, such as account login details, passwords and account numbers. A variation of phishing is SMS phishing (or smishing) where a fraudster sends a text message that asks a mobile phone user to provide personal information, such as their online banking password, or asks the phone user to make a phone call to a number controlled by the fraudster and then enter their ATM PIN number or online password.

Whaling – is a variation of phishing, but targets or ‘spears’ a specific subset of consumers, customers or employees. Fraudsters send tailored messages that appear to have come from the targeted entity’s organisation, sent by another staff member, known business partner or other trusted party. This can also be referred to as ‘spear-phishing’.

Pharming – redirects website traffic to an illegal site where customers unknowingly enter their personal data.

Triangulation – this enables fraudsters to steal credit card information from valid customers, typically through online auctions, ticketing sites, or online classified ads. A fraudster posts a product online at a severely discounted price, which is purchased by a customer using a valid credit card. The fraudster uses other stolen payment credentials to purchase and ship the product from a legitimate website to the customer. Neither the merchant nor the customer suspects anything, yet both have been duped. In the meantime, the fraudster now has access to the unsuspecting buyer’s card number and can continue to steal and amass other credit card numbers using the same scheme.

As in any other industry, disruption has the potential to be a force for good; it opens up opportunities through innovation. However, payments involve a complex web of interactions and APIs, which while creating opportunities for stakeholders, must now be a consideration in fraud terms. The identity network is also a driving force that, used well, can build trust, but also adds into this heady mix opportunities for fraud.

Cybercriminals are always one step ahead. They use a mix of social engineering and technology know-how to circumvent systems. Fraudsters’ ultimate aim is financial, so payment systems are the ideal target. Understanding the threat landscape is crucial to reinforcing protection, whilst keeping innovation clear of exploitation.