Trumpeter Jason Logue walks to centre stage, and begins his solo halfway through “Meanwhile Tomorrow,” one of the tracks on The Twelfth of Never by the Toronto world jazz group Manteca. Behind him, Doug Wilde’s piano accompaniment wraps itself around Logue’s playing. It’s a close facsimile of what band members would do in a live performance.

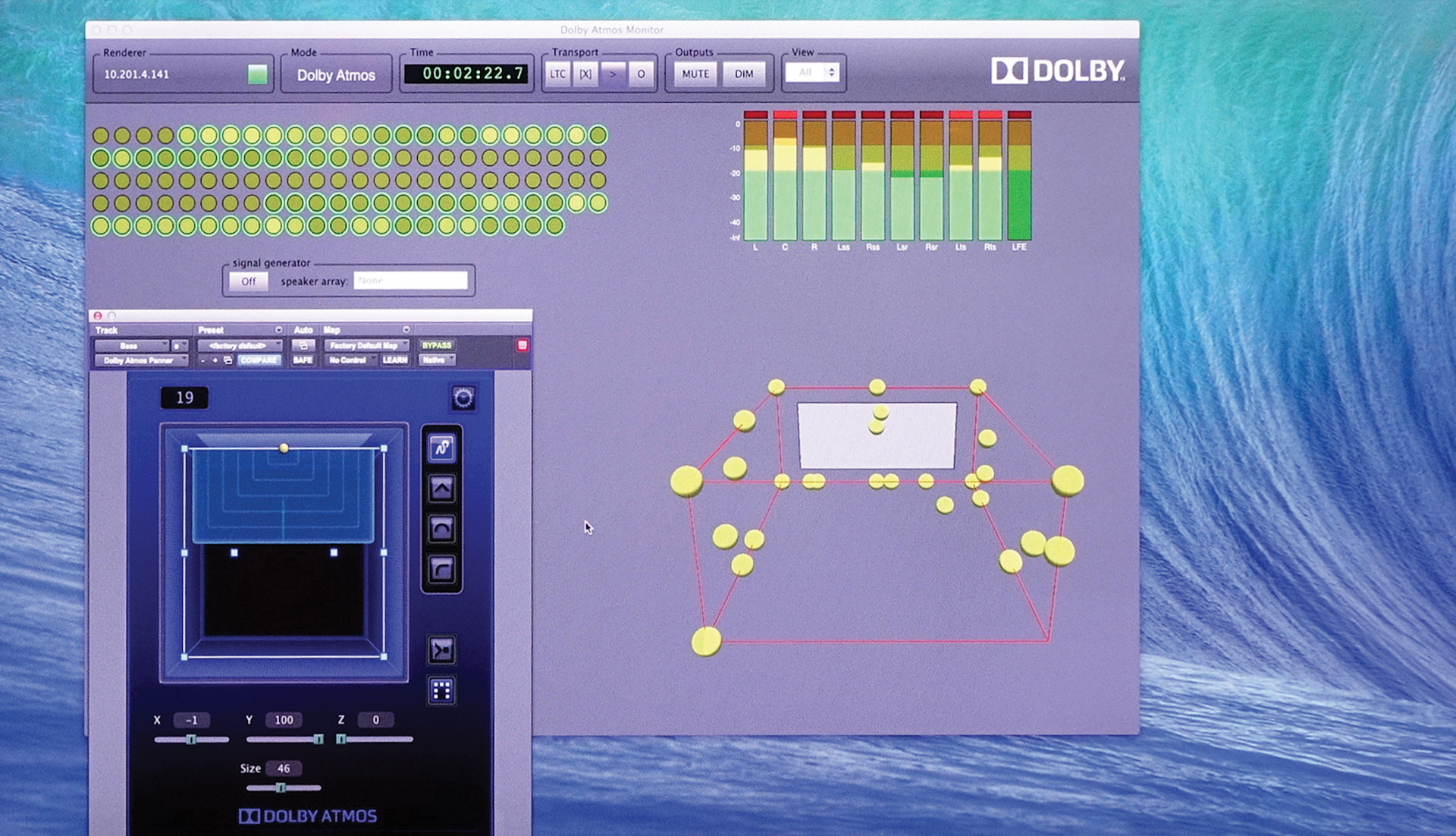

Except, this isn’t a live performance. While Logue’s solo is very real, his walk to the centre stage microphone is entirely virtual – an effect carefully created in a mixing studio at CTV Toronto. What I’m hearing, along with 50 other invited guests, is a Dolby Atmos rendering of the group’s 12th album, played through a 7.2.4 surround system at Revolution Recording in Toronto’s east end.

The event took place in the Studio A live room, where the album was recorded. For the seven floor channels, the organizers used Neumann studio monitors mounted at ear level. The four height channels were produced by Neumann monitors on boom stands, about 10 feet off the ground. A pair of Neumann subwoofers filled in the bottom octaves.

The mix was an experiment undertaken principally by Michael Nunan, Senior Manager, Broadcast Operations, Audio for Bell Media Inc., which operates several broadcast and specialty TV networks, including CTV, CityTV, TSN and Discovery Canada.

I was struck by how fun and involving it sounded, and by how tastefully the technology was used. Some effects were natural, such as horn players doing a virtual walk to centre stage for their solos. There were also effects that you’d never encounter in a live performance: percussion instruments elevated well above ear level off to the side or rear; and chirping guitar intros that flitted about the room above the audience. They were entertaining and engaging, but never gimmicky.

As bandleader and percussionist Matt Zimbel comments, “This isn’t a stunt mix. Michael was very respectful of our two-channel mix. It’s a very musical approach.” It was also striking how clear and intelligible everything sounded. That shouldn’t come as a surprise when you consider that the rendered mix was being played through an 11-channel system. Atmos can place sounds not just in the speakers, but between them. As Nunan explained, a system like the one used for the Manteca event has 55 phantom-centre channels.

“Because of spatial unmasking, you can focus on an individual instrument in a way that would be extraordinarily hard with two-channel stereo,” he elaborates. “Yet cohesiveness does not suffer. It still feels very much like a performance of a piece of music.”

But spatial unmasking has a potential down- side, Zimbel notes. “I remember feeling panicked, because when you’re separating instruments like that, you can hear any differences in timing. This band is so tight after playing for 37 years that I had nothing to fear.”

Zimbel would love to release the Atmos mix on Blu-ray, but acknowledges that this is a long shot. The fact is that surround music is a niche within a niche; and instrumental jazz music in immersive surround is a smaller niche still. As Zimbel observes, an Atmos version of The Twelfth of Never on Blu-ray would be “an elitist project … very much for the one per cent.”

Even so, the project has a lot to say about where recorded music may be headed; and TV audio as well. It also says a lot about how recorded music has changed in the last five decades. And it may prefigure a time – not this year or next, but not in the distant future either – when immersive audio enters the musical mainstream.

A NEW REALITY

Purists may scoff at the idea of placing percussion above and behind listeners, or having staccato guitar riffs zip about the room. The high-fidelity ideal (and it’s a noble one) holds that recordings should capture as much of the live music experience as possible. That aesthetic, which held sway throughout the first half-century of sound recording, came from the “respectable” branch of the music business, the one that specialized in the classical repertoire (plus occasional dalliances with jazz).

Even in classical, music doesn’t always come from in front. Hector Berlioz (in his Grande Messe des Morts) and Gustav Mahler (in his Resurrection Symphony) used large off-stage brass choirs to startling effect, announcing the Day of Judgement.

Popular musicians started exploiting surround during the quadriphonic era in the 1970s. But before Alan Parsons blew listeners’ minds with the explosion of chimes and alarm clocks in Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, music was under-going a sea change.

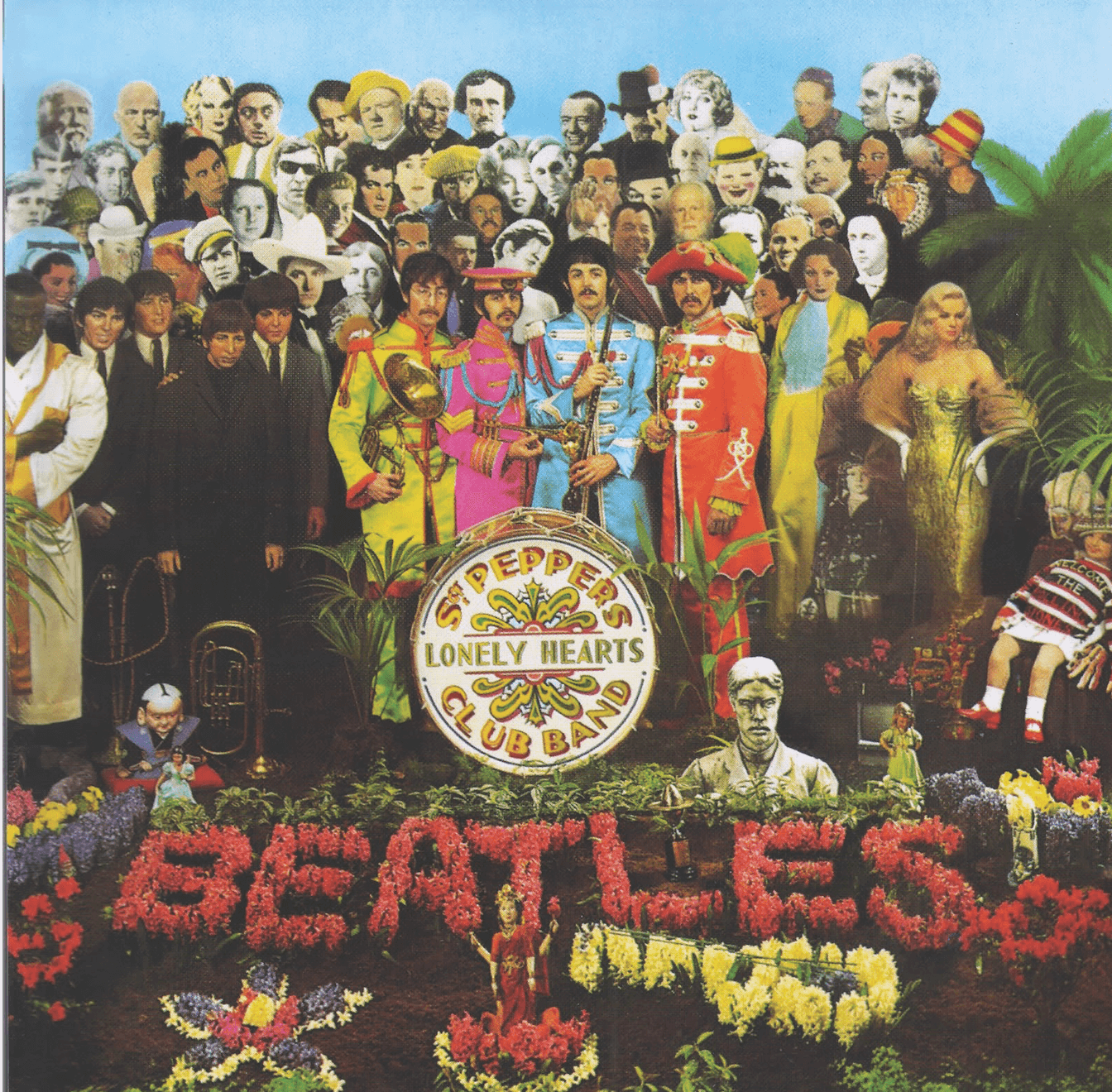

The pivotal event, essentially kicking off recording’s second half-century, was the release 52 years ago of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Made after The Beatles stopped touring, the album is wholly an artifact of the studio, with no roots in live performance. After Sgt. Pepper, the studio was where most musicians created new music. The recording became the original event; concerts became the facsimile.

I’m sure most readers know about the new stereo mix of Sgt. Pepper, created for the album’s 50th anniversary by Giles Martin, son of Sir George Martin, who produced most of The Beatles’ music. I suspect many of you have bought the new version on CD or vinyl, and (like me) found it to be a revelation.

That’s not just because more care has been taken on the two-channel mix (the Beatles and George Martin were closely involved in the mono mix, but the stereo mix was left to a senior engineer at EMI). It’s because with the new mix, Giles Martin was able to surmount some of the technological limitations the Beatles faced five decades ago. They recorded onto four-track tape, and then dubbed those tracks onto another tape while recording additional elements. With each generation, sound quality was degraded.

For the new mix, Giles Martin was able to go back to the original tapes and remix them on a digital workstation, avoiding the generational losses that resulted from bouncing tracks. As a result, the new mix is much more dramatic and harder-hitting than the original.

Giles Martin also made a 5.1 surround mix, released in Dolby TrueHD and DTS:HD Master Audio on Blu-ray, and Dolby Digital and DTS on DVD. The younger Martin also made an Atmos mix, which was presented by Apple Records and Universal Music in several Atmos- equipped cinemas in the U.S. and Canada.

Sadly, there are no plans to release the Atmos mix of Sgt. Pepper. I’d have loved to attend the presentation, but only learned about it after the one-time event. Judging by Mark Fleischmann’s online report for Sound & Vision, the Atmos mix was revelatory.

“I had a visceral sense of being in a large and solidly constructed bubble where events were beyond my control, bending my sense of reality out of shape,” Fleischmann writes. “My aesthetics became just as unhinged, because songs I’d always thought of as flimsy little geegaws suddenly grabbed me by the throat. ‘Good Morning Good Morning’ went from suburban dyspepsia to savage beat-down. ‘Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite’ was a carnival hallucination, like being trapped on a merry-go-round spinning just a little too fast for comfort.”

Fleischmann contrasts this aesthetic with “natural surround,” which places musicians in the front channels, and hall reflections and applause in the surrounds. “A natural mix is ideal for classical music,” he writes. “The other kind of mix, and the one employed in the new Sgt. Pepper, is what I call a dreamscape mix. … This is a far riskier strategy. But it is the ideal one for an album like Sgt. Pepper, which has never been anything but a dreamscape, whether mixed in mono, stereo, or surround.”

LEARNING EXERCISE

A dreamscape: that doesn’t sound far off Zimbel’s description of what Nunan had in mind for The Twelfth of Never. “Michael wanted to create a world,” he says, “and make our mix work in that space.”

The project dates back to the 2015 Pan Am Games in Toronto, for which Bell Media served as host broadcaster. Zimbel was involved in the opening and closing ceremonies, and Manteca played a couple of outdoor concerts as part of the Panamania Arts & Culture Celebration. Zimbel was having a coffee with Nunan and Anthony Montano, another senior audio engineer at Bell Media, in a mobile production truck in the bowels of Toronto’s Rogers Centre. When Zimbel mentioned that Manteca was working on a new album, Montano and Nunan asked if the band would be interested in doing a surround version.

“I thought it would be impractical for home playback,” Zimbel relates. “Who has that many speakers? Anthony explained how Atmos spatially understands the content and reconfigures it for the home.”

Nunan’s interest in the project was both personal and professional. “Like many engineers, Anthony and I do jobs on the side,” he says. “And since most working audio engineers would rather do music if they could make a living at it, there’s a natural connection between our advocacy for surround and our interest in exploring that leading edge.”

Part of Nunan’s day job at Bell Media is preparing music for the company’s shows, which range from live sports on TSN to documentaries on Discovery Canada. “Right from the moment when we have musicians on the stage,” he says, “we understand that we’re going to create real surround sound. And we’re going to preserve that multi-channel content all the way through the production chain, so that the microphone that was downstage left capturing the sound of the orchestra in the hall is going to end up in someone’s living room. That’s very unusual in the broadcast world.”

Like broadcasters throughout much of the world, Bell Media is preparing for the transformation to Ultra High Definition. The European Broadcast Union has specified MPEG-H as the audio codec for its UHD standard. In North America, Dolby AC-4 is being proposed as the audio codec for the ATSC 3.0 UHD standard.

“Both these systems can do a whole bunch of things,” Nunan explains, “some of them far beyond what is currently possible with Atmos. We started working with Atmos not because we think there’s a future in it for us as broadcasters, but because it was a way to start learning about how to work in high-order surround.”

With traditional channel-based surround audio, sound engineers place sounds like voices, instruments and special effects in discrete channels, spread them between channels, or pan from one channel to another. With object-based audio, the sound engineer uses a trackball controller to move individual sounds (called objects) on the screen, in front of, beside, behind or above the listener. In addition to the object’s location in a 360-degree sound-field, the engineer can assign properties such as loudness (level) and size (divergence).

For playback, a full-blown immersive audio playback system will have height speakers for producing sounds above the listeners. Multiple configurations are possible. During playback, the audio processor maps objects to the specific speaker layout.

“There’s a seismic shift between working in channel-based versus object-based audio,” Nunan says. “For one show here and one show there, we’d figure it out. But when you have a very high sustained operational tempo and a huge enterprise-scale operation, small differences can pile up. So, we wanted to start figuring out the workflow issues.”

SHOW AND TELL

The Manteca project was an opportunity to do just that. During the winter of 2016, the band laid down the album’s eight tracks, under the technical direction of Juno Award-winning recording engineer Jeff Wolpert. Wolpert is Co-owner of Desert Fish Studios, a mixing studio in downtown Toronto, and also an Adjunct Professor at University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music, where he runs a Master’s program in Musical Technology and Digital Media.

Instead of placing the nine band members in isolation booths, as he had done for previous Manteca albums, he had them play together on the floor of the main studio at Revolution Recording. Wolpert divided the studio with a tall baffle, placing the drums and rhythm section on one side, and horns on the other. He close-mic’d the musicians, and also used additional microphones for room ambience.

The baffle had glass that let the players see each other while recording. “Everybody played live at the same time,” Wolpert says, “which is good, because it gives the album a little more vibe. It’s basically a live-off-the-floor record.” Wolpert took the recorded tracks back to Desert Fish Studios, where he created the two-channel mix that would be used for the CD and online releases of the album.

Shortly after that, Nunan invited Wolpert and Zimbel to a show-and-tell at the largest post-production sound theatre on CTV Toronto’s Scarborough campus. The room was constructed in 2009 during the lead-up to the Vancouver Winter Olympics. In late 2014, Nunan successfully lobbied his employer to upgrade the room from 5.1 to 13.2 channels, so that he could begin experimenting with object-based surround.

“Once we had the room finished, as an ongoing rainy-day project, we tried to find out what it’s like to do a hockey game in here, or the Juno Awards, or one of our documentaries – all the various genres we work in. And by night, some of us started thinking, this is a really interesting envelope to work with music in.” Which led to the invitation to Wolpert and Zimbel.

To prepare for the presentation, Wolpert assembled the sound files for one of the album’s songs, “Meanwhile Tomorrow,” and made them available for Nunan to download. Everyone wanted the Atmos mix to be true to Wolpert’s two-channel mix, which Zimbel had just approved. With that in mind, Wolpert “flattened” the files, embedding the adjustments he had made to the sounds of the various instruments while making the stereo mix.

Nunan and Wolpert spent an evening at CTV Toronto experimenting with the mix. “Michael figured out what he thought would work best,” Wolpert relates, “and then I asked for changes, like having a little more snare drum to reestablish the original balance. Then we tried a few movement things and got it to a place where we thought it was cool.” Now it was time to invite Zimbel up for a listen.

MAKING MUSIC MOVE

Neither Zimbel nor Wolpert had any experience with object-based surround, although Wolpert has done channel-based surround music for film and mastered an Anne Murray album in surround, for release on DVD-Audio. But everyone in the room had clear ideas how the technology should – and shouldn’t – be used for The Twelfth of Never.

“Probably the most difficult part of the whole equation was to develop a conceit,” Nunan says. “What are people supposed to experience and why? They’re not in the perfect seat in a concert hall listening to Manteca perform. You’re not standing in the middle of the band. It was super important for Matt to develop a way of thinking about how we were going to explore these compositions.”

Wolpert and Zimbel had the idea of breaking songs into “scenes”: intro, verse, chorus, bridge, et cetera. “Each section of the tune now becomes a new scene,” Wolpert explains. “They’re related but they’re different.” Adds Zimbel: “It’s like a lighting director would light a stage performance. The scene evolves as the song evolves. You have a different scene for solos, where the soloist will move to a downstage to a solo mic.”

Nunan went with the idea. He’d move objects (i.e. instruments) between scenes as the song evolved, but also within scenes. “In some cases, we let Colleen on saxophone walk to centre stage as she was playing, as a continuous organic movement. In other cases, there had been three bars since you heard her, so when she next appears, the spotlight finds her on her mark.

“We also discovered where there could be exceptions to those rules,” Nunan continues. “There are moments where two feature instruments are playing almost simultaneously: almost call and response. We concluded that the best effect was to separate them as widely as possible to let the audience better understand the interplay between them, in a way that you would never do in a traditional two-channel stereo mix.”

Nunan wanted the mix to be fun, but not gimmicky. “Some people will make things fly around the room and nauseate everyone,” he elaborates. “But that doesn’t mean that things have to be pedestrian. Some sounds are very static. Other sounds by their nature implicate movement. All right: let’s see what happens when we actually move them.”

But as Wolpert notes, it’s important not to overdo movement. “You really can only track one thing moving. That’s why that whole pack-hunting thing gets us every time, right? Too many moving things, and we’re finished. And moving stereo items in rotation doesn’t work very well at all. We just aren’t built to perceive that sort of stuff.”

Wolpert also had ideas about where objects should go. Important elements like vocals should go in the front. But you can shift other elements such as drums to the side or rear. “There are things one doesn’t expect to be in the back,” he comments, “but that’s never a good reason not to do it.”

As Wolpert notes, percussive sounds are very easy to localize. “If you want to make a big deal out of the surrounds, putting percussion there does it. But you have to be careful about pulling people out of the experience, activating the exit-sign effect where people look around to see where a sound is coming from.”

On the other hand, Wolpert likes to spread out lush sustained notes, wrapping them from the fronts to the surrounds. “With these sounds, it’s less about the location than the feeling,” he explains. “You create a space, and it’s a lovely space.”

After a couple of evenings of listening and discussion, Zimbel gave Nunan the green light. Through the spring and summer of 2016, Wolpert prepared the files for the seven remaining songs for Nunan to download. Some songs were as many as 60 tracks wide, so mixing them was a major undertaking. By mid-October, Nunan had finished the project.

For most of the band, the event at Revolution was the first time they heard the Atmos mix. “In general, the whole band liked it,” Wolpert recalls. “One of the band members was surprised by how it changed the emotion of the songs, which I really twigged onto. That’s a tool I’ve never had before. I can make things louder and quieter; I can change tone and dynamics and a million other things. But this is something that can create emotion, and that’s not easy to find.”

IF A TREE FALLS IN THE FOREST …

The question is, other than the people at that event last fall, who will ever hear this mix? And who will ever hear the Atmos mix of Sgt. Pepper, other than the fortunate few who attended the one day presentation? These experiments are fun, but will they ever find an audience?

The fact is that surround music has always been a tough sell. Blu-ray concerts have a following but surround music without video has never found much of an audience. There was some initial enthusiasm about quadriphonic in the 1970s, but it quickly fizzled out. DVD-Audio disappeared after a few years in the market in the 2000s. Super Audio CD persists, mainly in the classical realm, but it’s a tiny niche.

Nunan thinks the Manteca project was worth doing regardless of audience size. “If all we got was the ability to deliver this immersive experience of a piece of music into the listening rooms of the very small percentage of the public who have seven, eight, 10, 11, or 12 loudspeakers in their living room, I still think that’s worthwhile.”

More importantly, object-oriented formats allow engineers to create programming that will play on many different platforms, from a full-blown $50,000 Atmos theatre, to a standard 5.1-channel Dolby Digital setup, to 3” paper speakers inside a flat panel. That helps explain why Bell Media has been so supportive of Nunan’s experiments.

And as Steve Jobs liked to say, “there’s one more thing.” Seventy-two hours before I met with Nunan at CTV, he had received software for rendering binaural versions of an Atmos program, and then spent most of a weekend playing with it. Intended strictly for headphone listening, binaural recordings of live events are made by putting a dummy head with microphones in its ears in best seat in the house. A listener wearing headphones will hear what he would have heard if he had been in the same seat as the dummy head.

I’ve heard true binaural a few times, and it’s wild. At Summer CES in Chicago many decades ago, Stax used a binaural recording of organ music to demonstrate its electrostatic headphones. The sound was completely outside of my head. I was transported to a French cathedral, hearing a performance of a Duruflé Suite.

True binaural recordings aren’t possible with multi-mic’d studio recordings. No matter: as I experienced for myself, a binaural rendering can be as transporting. Nunan had me sit in the sweet spot while he played “Purple Theory” through the 7.2.5 speaker setup in his studio. The instruments emerged from a 360-degree soundfield, completely divorced from the speakers. The horns were off to the right, percussion instruments played antiphonally behind me, and the keyboard played up front.

Next, he played a binaural rendering of the same song through Sennheiser HD 800 headphones and HDVD 800 headphone amplifier. The effect was just as impressive, with an immersive soundfield that was completely outside my head. Nunan then switched back and forth between ’phones and speakers. The HD 800 is an open-back headphone, and I found myself having to check whether I was hearing the ‘phones or speakers.

Humans use different cues to perceive direction: the relative timing of sounds at our two ears, and the way our heads and outer ears (pinnae) filter sounds coming from different directions. A binaural software engine applies the same kind of filtering to a Atmos bitstream, tricking our ear- brain into perceiving objects “out there.”

There are two ways to deliver this experience to headphone listeners. Content providers could offer a binaural version of their programming, or (more likely) deliver a bitstream that can be rendered binaurally in real-time by software on the listener’s device.

Comments Nunan: “Right now, the person who’s watching something on CraveTV or Netflix on an iPhone and listening through headphones represents the worst-case scenario for us. As a sound professional, that’s not how I want people to experience my documentaries and concerts. But if this becomes a reality, I can create the next Manteca record or a documentary for Discovery and push that out into the world, such that someone who’s capturing it in a $50,000 home theatre gets an extraordinary experience. The person two doors down listening with an older 5.1 AVR gets a great experience entirely in keeping with their expectations. Way down, the guy with the earbuds goes from being the worst-case scenario to being the second-best case, because short of having all those loudspeakers, that’s the only way you’re going to get this sense of space. I have a hard time believing anyone is going to have a compelling argument against me doing this.

“For the past 20 years, surround music has been a very marginal proposition,” he concludes. “But I think this could be the start of some real excitement about surround music, especially since this technology, not just Atmos, but AC-4, MPEG-H and DTS:X, divorces the creation environment from the consumption environment in a way that we’ve never had before. I like our chances.”